This work was performed with my colleague Sylvain Pelissier. We demonstrated that the EdDSA signature scheme is vulnerable to single fault attacks, and mounted such an attack against the Ed25519 scheme running on an Arduino Nano board. We presented a paper on the topic at FDTC 2017, last week in Taipei.

As you all know, ECDSA is known for being the elliptic curve counterpart of the digital signature algorithm DSA. ECDSA is also notably known because of the PlayStation 3 hack in which an ECDSA private key could be retrieved because ECDSA wasn’t properly randomized.

ECDSA is also used by Bitcoin to sign the transactions and data. In 2013, over 59 bitcoins (which were then moved when bitcoin crossed the $4,400 line in August 2017) were stolen because of the same weakness as in PS3’s: many Android Bitcoin wallets were relying on a weak random generator to produce their $k$ when signing transaction. This allowed an attacker to recover these wallets’ private keys and thus to empty those compromised wallets.

Researchers have asked themselves how could data be signed without relying on a random generator, hence avoiding randomness-failure of this sort. A few answers came out, with — most notably — RFC6979, which introduced a deterministic version of ECDSA to avoid those problems.

This deterministic version of ECDSA proved to be vulnerable to fault attacks because signing two different messages with the same $k$ is still as deadly as with the normal version, and a fault after the deterministic generation of $k$ can lead to signing different data with the same $k$; which in turn allows to recover the private key, as previously seen.

EdDSA is another deterministic elliptic curve signature scheme, described in RFC8032. EdDSA works over twisted Edwards curves, which have a few nice properties. For example, those curves have fast and complete addition formulas, which means one formula can be used with all pairs of possible inputs and also for doubling a point. The most used twisted Edwards curve is probably the one birationally equivalent to the Montgomery curve “Curve25519”, since it is at the core of the “Ed25519” signature scheme. This scheme is one of the two explicit variants of EdDSA defined in RFC8032. EdDSA is built in order to be immune to most of the common attacks plaguing ECDSA and other signatures schemes, but they both also rely on a deterministic generation of their $r$ parameter (which corresponds to the ECDSA’s $k$ parameter) using a hash function $H$.

What’s more, Ed25519 is especially interesting because it notably features the followings (quoted from its homepage):

All of those features render the Ed25519 signature scheme really interesting, even on embedded devices.

- Fast single-signature verification.

- Very fast signing.

- Collision resilience. Hash-function collisions do not break this system. This adds a layer of defense against the possibility of weakness in the selected hash function.

- Foolproof session keys. Signatures are generated deterministically; key generation consumes new randomness but new signatures do not. This is not only a speed feature but also a security feature, directly relevant to the recent collapse of the Sony PlayStation 3 security system.

- Small signatures. Signatures fit into 64 bytes.

- Small keys. Public keys consume only 32 bytes.

Attacking EdDSA with faults

But EdDSA, and Ed25519, are still compromised if two different messages are signed using the same value for $r$. This is obviously impossible in theory, since $r$ is produced deterministically as follows: $ r=H(h_b, \ldots, h_{2b-1},M)$, for the hash $H(K)=(h_0,h_1,..., h_{2b-1})$ of the $b$-bit secret string $K$, and for $M$ the message.Once $r$ has been deterministically generated, the signature is generated in two steps:

- Define the first part $R=rB$, for $B$ the base point of the elliptic curve at hand and $r$ as defined above;

- Define the second part $S=(r + H(R,A,M)a)\mod \ell$, for $ell$ the order of $B$, and $A = aB$ the public key, where $a$ is determined as: $a = 2^{b-2}+\sum_{3\leq i \leq b-3} 2^ih_i$

Problems arise when the value $r$ is either reused to produce $S$ for another message or is not secret. The first case can be spotted thanks to the public value $R=rB$, since it will be the same if $r$ is reused, we discuss how to recover secret key material from $r$ reuses below. In the second case, an attacker can simply use the knowledge of that value to compute: $(S-r)(H(R,A,M))^{-1} = a \mod \ell$ and obtain the secret value $a$, which in turn can be used to forge valid signatures using the following procedure:

- Define the first part $R=rB$, with $r$ any random value of her choice;

- Define the second part $S=(r+H(R,A,M)a) \mod \ell$, just like before.

So $r$ has to be kept secret.

What happens if you were to twice sign the same message $M$? It would output the same signature $(R,S)$ both time, as previously explained. Unless an error occurred at some point during the signature generation. More precisely, what if an error occurs during the computation of $H(R,A,M)$ in $S=(r + H(R,A,M)a)\mod \ell$, producing a $S’$ instead?

We would then have a different, invalid, value $S’$ instead of $S$ and the resulting signature would be $(R, S’)$. Then the verification of that signature against the known message $M$ would fail, of course. But if the attacker were to know the kind of error which happened and the correct signature $(R, S)$, she could also possibly recover the value $a$ by computing $a=(S-S’)(h-h’)^{-1} \mod \ell$ and so be able to perform the exact same attack we described above!

This means that we can recover enough of the secret key material with a single glitch in the signature computation to compromise the system.

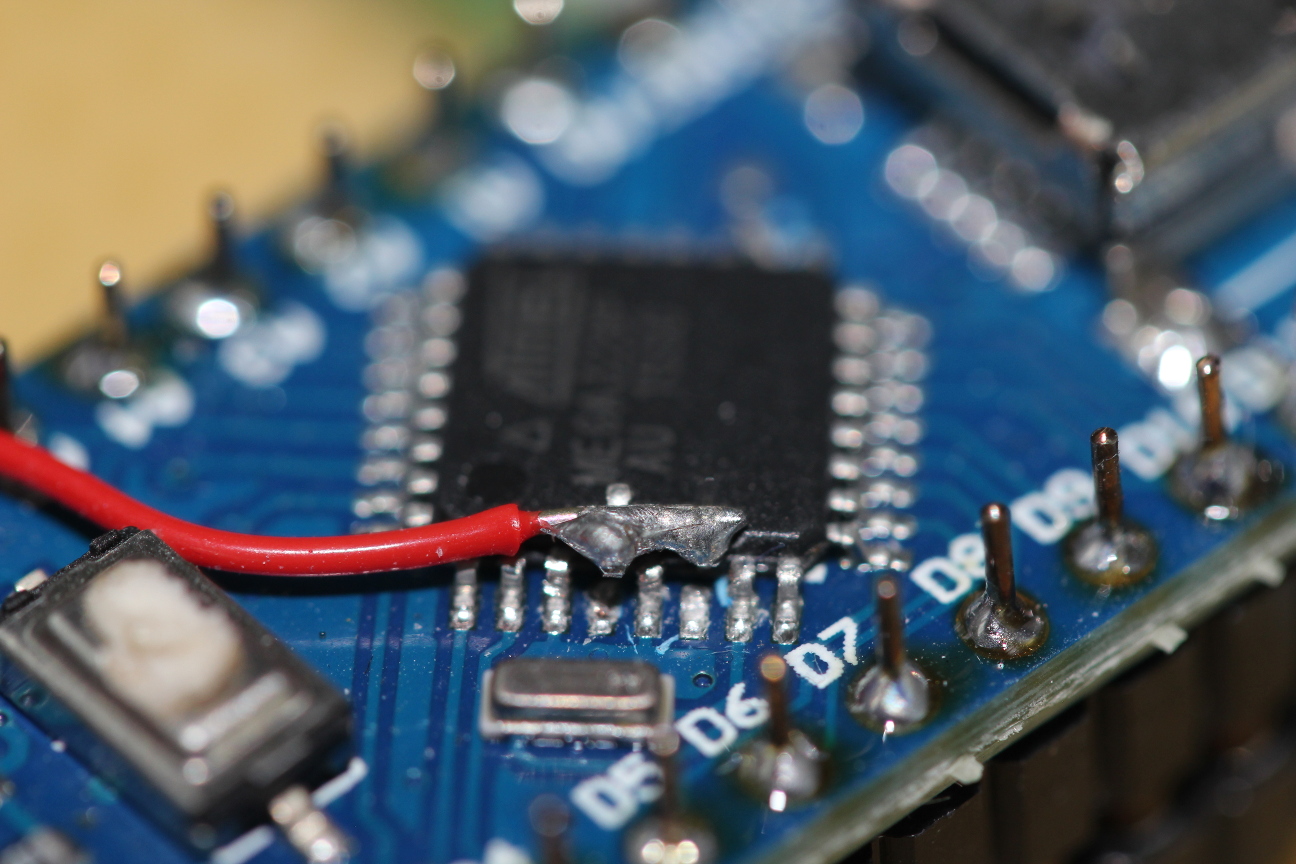

We demonstrated it on an Arduino Nano, using the Arduino Libs’ Crypto Ed25519 implementation and simple voltage glitches. We were able to cause single byte random errors at the end of the computation of $H(R,A,M)$, allowing us to efficiently brute-force the error location and value, thus recovering half of the secret key. This allowed us to generate seemingly valid signatures for any message, thanks to randomly generated $r$ values, in a way that is indistinguishable from the real signer to the verifier, since the value $r$ has to be kept secret by the signer.

Want to try it at home? Our code is freely available online on our Github. We also have a software version, simulating the actual faults, in case you don’t have the necessary hardware to perform VCC glitches. Plus the code of the brute force recovery of the secret value, which simply needs two signatures of the same message, a faulted signature and a valid one, to retrieve the secret, if there was a single byte error in the computation.

If you want to learn more details, read our paper, in which we also proposed a novel so-called “infective countermeasure” to avoid falling for such faults, while keeping full compatibility with the EdDSA standard (contrary to the countermeasure consisting in a fall back to a randomized $r$ value.)